The Specter in the Machine:

The Invisible Architecture of Algorithmic Control

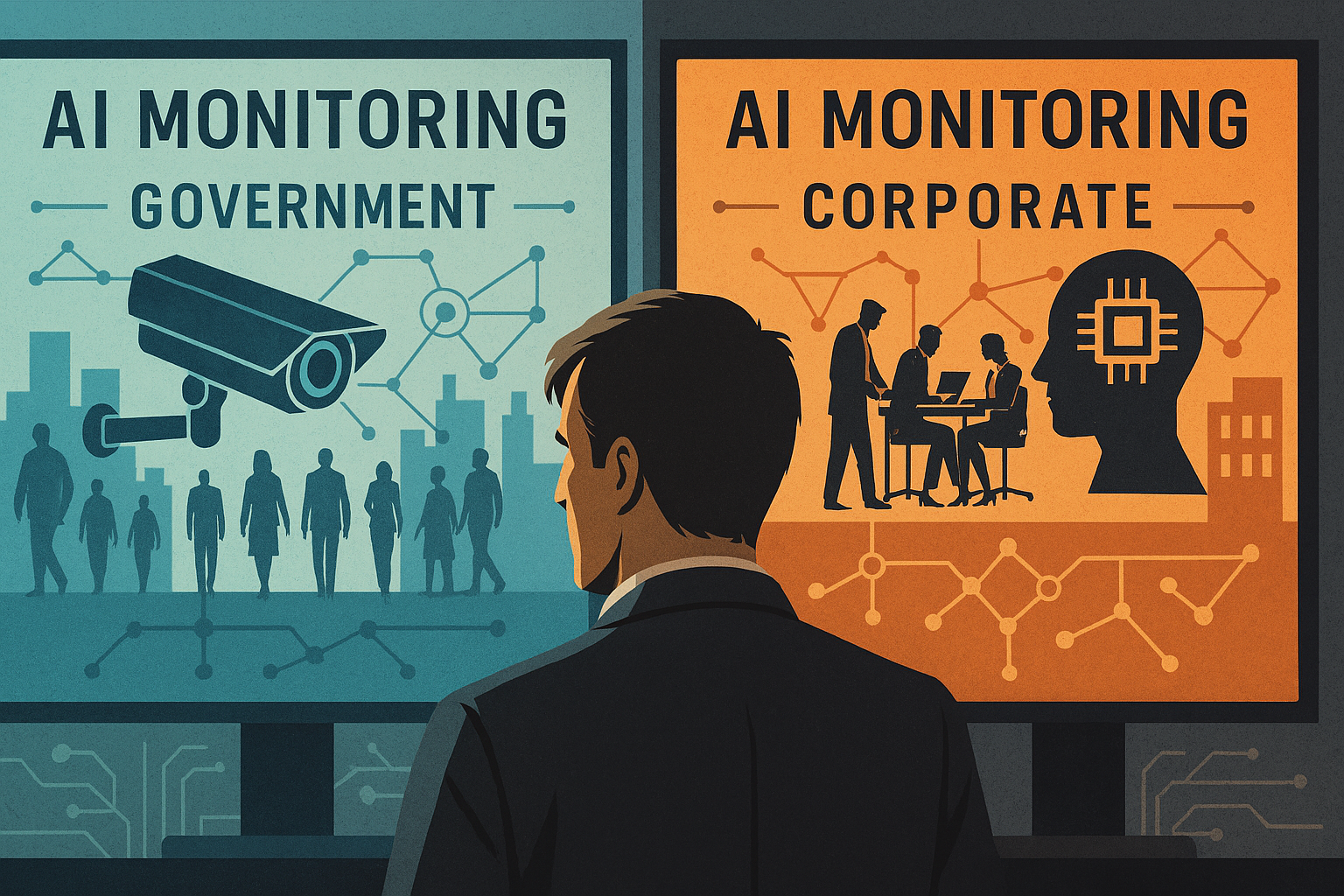

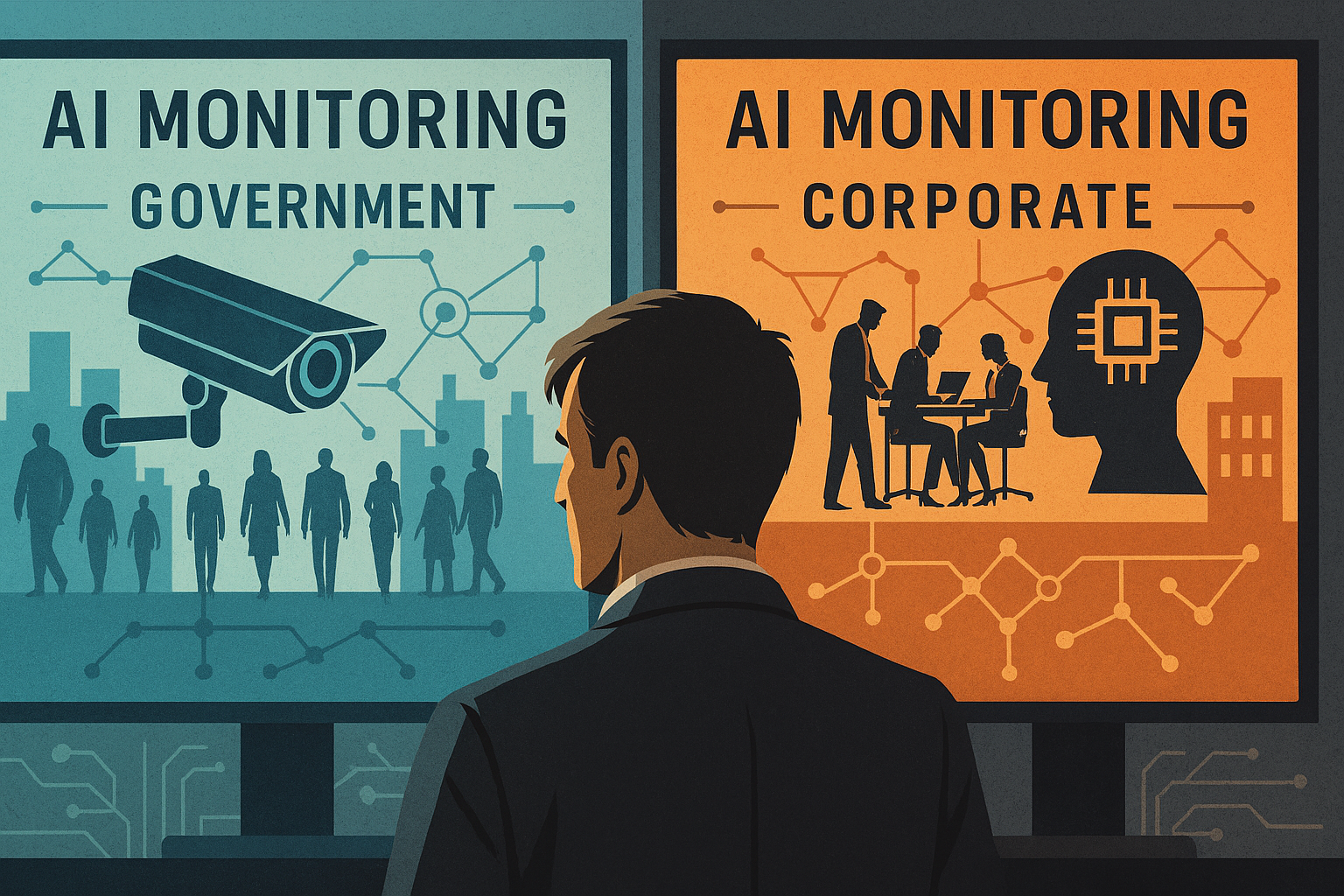

Algorithmic systems increasingly mediate access to work, credit, information, healthcare, security, and public services. While these systems are often presented as neutral tools designed to optimize efficiency, their growing role in governance raises deeper questions about power, accountability, and democratic oversight.

This investigation examines how algorithmic decision-making infrastructures have quietly evolved into mechanisms of control—shaping outcomes at scale while remaining largely opaque to the citizens they affect. Drawing on academic research, regulatory documents, and documented real-world cases, it traces the emergence of what can be described as an invisible architecture of algorithmic governance.

From Automation to Authority

Early uses of algorithms in public and private institutions focused on automation: sorting data, streamlining workflows, and accelerating administrative processes. Over time, however, these systems began to assume a more authoritative role—making or heavily influencing decisions that directly affect human lives.

In domains ranging from predictive policing to welfare allocation and credit scoring, algorithmic models now participate in judgments that were once the sole responsibility of human officials. Research by ProPublica revealed as early as 2016 that risk assessment algorithms used in the U.S. criminal justice system exhibited significant racial bias, despite claims of objectivity.

Similar concerns have emerged in Europe. Studies conducted by the AlgorithmWatch project have documented how automated systems are increasingly deployed by public authorities with limited transparency and minimal mechanisms for contestation. In many cases, affected individuals are unaware that an algorithmic system was involved in the decision at all.

This shift—from automation to authority—marks a critical transformation. Algorithms are no longer merely tools assisting governance; they are becoming embedded actors within it, exercising a form of power that is procedural, statistical, and often inscrutable.

Opacity by Design

One of the defining characteristics of contemporary algorithmic governance is opacity. While these systems are often described as complex, their lack of transparency is rarely accidental. In many cases, opacity is a structural feature—produced by technical design choices, institutional incentives, and legal protections.

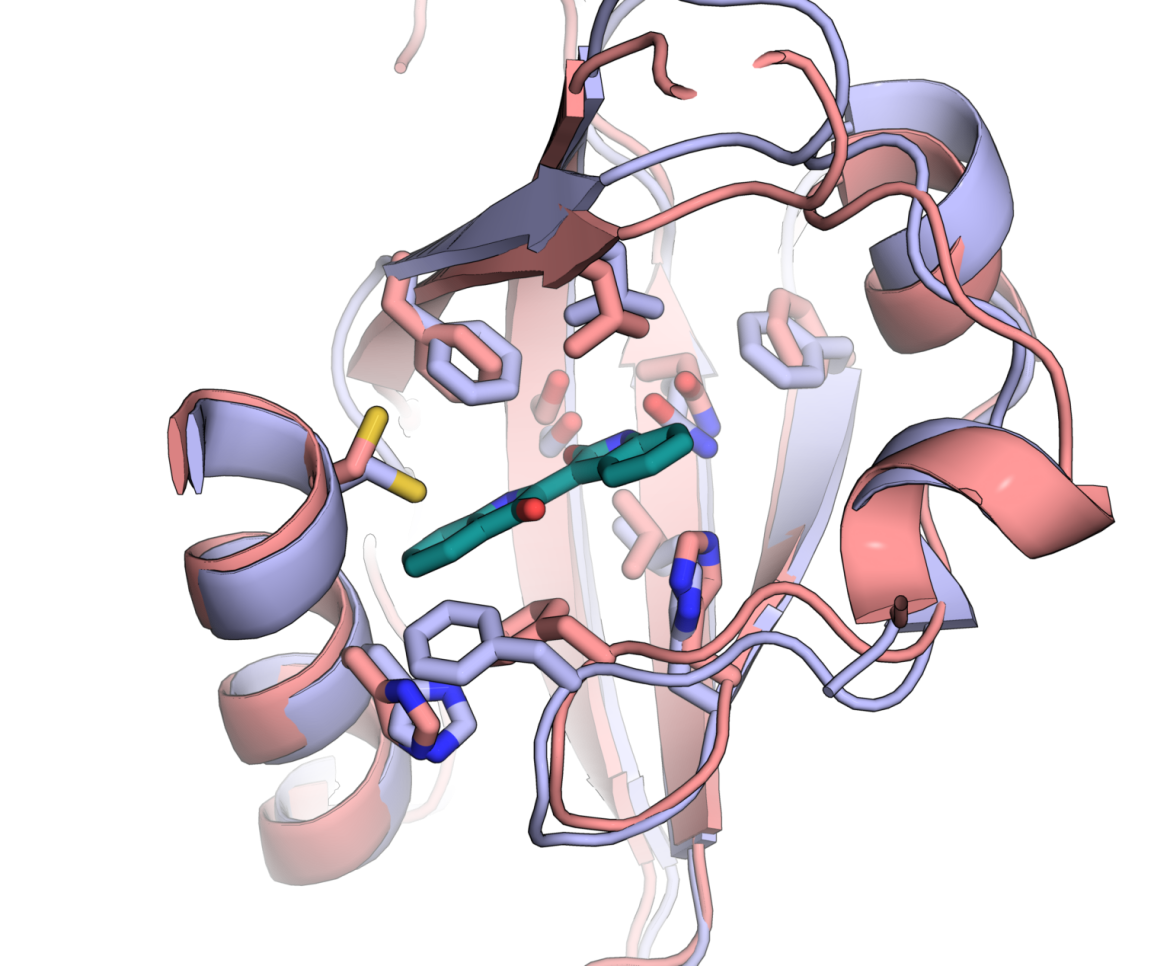

Machine learning models, particularly those based on deep neural networks, are frequently described as “black boxes”: systems whose internal logic is difficult or impossible to interpret even for their creators. Research from the journal Nature Machine Intelligence has shown that increasing model accuracy often comes at the cost of interpretability, creating systems that perform well statistically while remaining opaque in practice.

This technical opacity is reinforced by legal and commercial frameworks. Private vendors supplying algorithmic systems to governments routinely invoke trade secret protections to avoid disclosing how their models operate. In the United States, courts have repeatedly upheld such claims, including in cases involving risk assessment tools used in criminal sentencing, as documented by the Electronic Frontier Foundation .

The result is a profound accountability gap. Individuals affected by algorithmic decisions may be denied credit, benefits, or freedom without access to meaningful explanations. Even when errors are suspected, the combination of technical complexity and proprietary secrecy makes challenging these systems exceptionally difficult.

European regulators have increasingly acknowledged this problem. The European Commission’s proposed AI Act introduces obligations around transparency and human oversight for high-risk systems. Yet critics argue that many of its provisions remain insufficient to pierce the deepest layers of algorithmic opacity, particularly when systems are developed and controlled by multinational technology firms.

Opacity, then, is not merely a technical limitation. It is a political condition—one that redistributes power away from citizens and public institutions toward those who design, own, and operate algorithmic infrastructures.

When States Delegate Power to Machines

Across democratic societies, governments increasingly rely on algorithmic systems to make or inform decisions once reserved for human judgment. From welfare distribution to border control and predictive policing, these technologies are often introduced in the name of efficiency, objectivity, and cost reduction.

In practice, however, delegation to machines has frequently amplified existing inequalities. One of the most widely cited examples is the Dutch welfare fraud detection system known as SyRI. In 2020, a court in The Hague ruled that the system violated human rights, citing its lack of transparency and disproportionate impact on low-income and migrant communities. The case is documented in detail by the Dutch judiciary .

Similar dynamics have emerged in the United Kingdom, where automated systems were used to assess visa applications and predict the likelihood of immigration overstays. A 2020 investigation by The Guardian revealed that a Home Office algorithm effectively embedded racial and nationality-based bias into immigration decisions, prompting its eventual withdrawal.

In the United States, algorithmic risk assessment tools are routinely used in criminal justice systems to inform bail, sentencing, and parole decisions. ProPublica’s landmark investigation into the COMPAS system found that Black defendants were significantly more likely than white defendants to be incorrectly labeled as high risk, raising serious concerns about fairness and due process (ProPublica) .

What unites these cases is not a single flawed algorithm, but a pattern of institutional abdication. By framing algorithmic outputs as neutral or scientific, public authorities often shift responsibility away from human decision-makers. Accountability becomes diffuse, contested, or entirely absent.

Political theorists have warned that this dynamic risks hollowing out democratic governance. As decisions become automated, the space for deliberation, contestation, and moral judgment narrows. What emerges is a form of rule by proxy—where power is exercised through systems that are formally technical but substantively political.

Platform Power and the Privatization of Governance

Beyond the state, algorithmic power is increasingly exercised by private technology platforms whose decisions shape public life at planetary scale. Companies such as Google, Meta, Amazon, and TikTok now operate infrastructures that function less like conventional businesses and more like systems of governance—setting rules, enforcing norms, and allocating visibility.

Search rankings determine which information is seen and which is buried. Recommendation engines shape political discourse, cultural consumption, and even collective memory. Content moderation systems decide, often automatically, what speech is amplified, restricted, or erased. As legal scholar Tarleton Gillespie has argued, platforms have become “custodians of the internet’s public spaces,” while remaining largely unaccountable to democratic oversight (Gillespie, Custodians of the Internet) .

This concentration of power is not merely cultural but deeply political. Investigations have shown how platform algorithms can influence electoral processes, sometimes unintentionally. A widely cited experiment conducted by psychologist Robert Epstein suggested that search engine rankings alone could shift undecided voters’ preferences without their awareness, a phenomenon he termed the “search engine manipulation effect” (PNAS) .

Social media platforms have likewise been implicated in the amplification of misinformation and political polarization. Internal documents leaked by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed that company executives were aware that engagement-driven algorithms could intensify social harm, yet often prioritized growth and profitability over mitigation efforts. The disclosures were reported extensively by The Wall Street Journal and later examined by the U.S. Congress.

Crucially, these governance functions are exercised without the procedural safeguards traditionally associated with public authority. Platform rules can change overnight. Appeals processes are opaque or inconsistent. Users—citizens, in effect—have limited recourse when automated systems restrict access, visibility, or participation.

The result is a quiet privatization of governance. Decisions with societal consequences are outsourced to proprietary systems optimized for engagement, efficiency, or profit, rather than democratic legitimacy. Power operates through code, but its effects are felt in elections, markets, and public debate.

From Surveillance to Prediction

Surveillance, in its classical sense, was about observation. In the algorithmic era, it has evolved into something more powerful: prediction. Contemporary data systems do not merely record past behavior; they are designed to anticipate, influence, and ultimately shape future actions.

This shift was articulated most prominently by Harvard Business School professor Shoshana Zuboff, who described the rise of what she termed “surveillance capitalism”—an economic logic that extracts behavioral data to predict and modify human behavior for profit (Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) . While her thesis has sparked debate, the underlying mechanics are now widely observable across digital platforms.

Every interaction—search queries, location data, biometric signals, purchase histories—feeds machine learning models trained to infer intent, preferences, and vulnerability. These systems assign probabilistic scores: likelihood to buy, to disengage, to default, to radicalize, or to comply. The individual is no longer treated as a subject with agency, but as a statistical profile in constant flux.

In the commercial sphere, this logic underpins targeted advertising and dynamic pricing. In the public sector, it increasingly informs predictive policing, risk assessment tools, and welfare eligibility systems. A report by the AI Now Institute documented how predictive systems deployed by governments often reproduce existing social inequalities while obscuring decision-making behind technical complexity (AI Now Institute) .

Predictive policing tools, such as those previously marketed by companies like PredPol, have been criticized for reinforcing feedback loops: police are sent where data suggests crime is likely, generating more data from the same neighborhoods and confirming the model’s initial assumptions. Multiple academic studies have questioned both the effectiveness and fairness of these systems (ProPublica) .

What distinguishes predictive systems from earlier forms of surveillance is their temporal orientation. Power no longer operates solely by reacting to behavior, but by pre-empting it. Choices are nudged before they are fully formed; opportunities are filtered before they appear.

In this context, control becomes anticipatory rather than coercive. The most effective systems do not need to command or prohibit. They simply reshape the environment in which decisions are made—quietly narrowing the range of imaginable futures.

Opacity, Bias, and the Illusion of Neutrality

Algorithmic systems are often presented as objective, neutral, and technically optimized. In practice, many operate as opaque decision-making machines whose inner logic is inaccessible not only to the public, but frequently to the institutions that deploy them.

This opacity is not accidental. Modern machine learning models—particularly deep neural networks—are valued precisely for their complexity and performance at scale. Yet that same complexity makes it difficult to explain how specific inputs lead to particular outcomes, a problem widely referred to as the “black box” effect.

Researchers at the European Commission have warned that opacity poses a direct challenge to democratic accountability when algorithmic systems are used in high-stakes contexts such as credit scoring, hiring, healthcare, and criminal justice (European Commission, Explainable AI) . Without meaningful transparency, affected individuals are often unable to understand, contest, or appeal automated decisions.

Bias is frequently framed as a technical flaw that can be corrected with better data. However, numerous studies suggest that algorithmic bias is often a reflection of structural inequalities embedded in historical records. When systems are trained on biased data, they learn and reproduce those patterns at scale.

A landmark investigation by ProPublica into the COMPAS risk assessment tool used in U.S. courts found that the system was significantly more likely to misclassify Black defendants as high risk, while underestimating risk for white defendants (ProPublica, “Machine Bias”) . The vendor disputed the findings, but independent audits have since echoed similar concerns across comparable tools.

The claim of neutrality often rests on the assumption that algorithms merely optimize for predefined objectives. Yet those objectives—what is measured, what is maximized, what is ignored—are human choices shaped by institutional priorities and power relations.

As legal scholar Frank Pasquale has argued, opacity can function as a form of power in itself, shielding corporate and governmental actors from scrutiny while shifting responsibility onto technical systems (The Black Box Society) . When decisions are attributed to “the algorithm,” accountability becomes diffuse and difficult to locate.

In this way, the illusion of neutrality serves a political function. It frames contested social outcomes as the product of technical necessity, rather than policy choice—closing off democratic debate at precisely the moment it is most needed.

Governance Without Visibility

As algorithmic systems increasingly shape public and private decision-making, governance frameworks have struggled to keep pace. In many jurisdictions, rules governing automated systems rely heavily on voluntary standards, self-regulation, or post hoc oversight—mechanisms that presuppose visibility into how systems actually function.

In practice, that visibility is often absent. Proprietary protections, trade secrets, and intellectual property claims routinely limit access to model architectures, training data, and performance metrics. Regulators are frequently asked to trust assurances of compliance without the technical or legal tools needed to verify them.

This dynamic has given rise to what scholars describe as “governance by delegation,” in which oversight responsibility is effectively outsourced to the same actors that design and deploy the systems (Nature Machine Intelligence) . The result is a regulatory asymmetry: those with the greatest informational power face the least external scrutiny.

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act represents the most ambitious attempt to date to address this imbalance. By introducing risk-based obligations, documentation requirements, and limited transparency mandates, the AI Act seeks to move beyond purely voluntary governance (EU AI Act) . Yet even its strongest provisions depend on enforcement capacities that many national authorities are still in the process of building.

Elsewhere, governance remains fragmented. In the United States, oversight is distributed across sector-specific agencies, executive orders, and nonbinding guidelines, creating gaps in accountability for systems that operate across domains (White House AI Bill of Rights) . In many parts of the Global South, regulatory frameworks are still emerging, often under pressure from international vendors and development institutions.

This lack of coherent oversight has concrete consequences. Automated welfare systems have incorrectly denied benefits to thousands of people in countries such as the Netherlands and Australia, with errors only discovered after significant public harm had already occurred (The Guardian, Robodebt) . In these cases, governance mechanisms failed not because rules were absent, but because systems were deployed faster than institutions could understand or supervise them.

Governance without visibility ultimately favors scale over accountability. It allows algorithmic systems to expand into sensitive social domains while shielding their operation from meaningful democratic oversight. The question is no longer whether regulation exists, but whether it can function when the objects it seeks to govern remain largely unseen.

The Human Cost of Automated Decisions

Behind the abstraction of models, scores, and automated workflows lie individuals whose lives are directly shaped by algorithmic decisions. In sectors such as welfare administration, migration control, criminal justice, and employment, automated systems increasingly determine access to resources, rights, and opportunities.

One of the most widely cited examples is the Dutch childcare benefits scandal, in which an automated fraud detection system disproportionately flagged low-income and migrant families for investigation. Thousands were falsely accused of fraud, forced to repay benefits they could not afford, and pushed into financial and psychological distress. The system operated for years before its discriminatory effects were fully acknowledged, ultimately contributing to the resignation of the Dutch government in 2021 (The Guardian) .

Similar dynamics have emerged in automated welfare systems elsewhere. In Australia, the “Robodebt” programme used algorithmic income averaging to identify alleged overpayments, issuing debt notices to hundreds of thousands of citizens. Independent reviews later found the system to be unlawful, with errors causing severe stress, financial hardship, and, in some cases, loss of life (ABC News) .

In the context of migration and border control, algorithmic risk assessment tools are increasingly used to prioritize inspections, allocate resources, or assess asylum claims. Critics argue that these systems often rely on proxy variables—such as nationality or travel history—that can encode structural biases while remaining opaque to those affected (Access Now) . For individuals subject to these systems, challenging an automated decision can be legally and practically difficult, particularly when the reasoning behind it is inaccessible.

The criminal justice system has also seen the widespread adoption of algorithmic risk assessment tools, particularly in sentencing and parole decisions. Studies of systems such as COMPAS have raised concerns about racial bias, error rates, and the use of proprietary models that defendants cannot meaningfully contest (ProPublica) . Here, automation does not eliminate discretion—it relocates it into technical systems that operate beyond public scrutiny.

Across these domains, a common pattern emerges: algorithmic systems are often introduced as efficiency tools, yet their errors are distributed unevenly. Those with the least social, economic, or legal power tend to bear the highest costs when systems fail. Appeals processes, where they exist, are frequently slow, opaque, or inaccessible, reinforcing existing inequalities rather than mitigating them.

The human cost of automated decision-making is not an unintended side effect; it is a predictable outcome of deploying high-impact systems without robust safeguards, transparency, and accountability. As automation expands, the central question is not whether these systems are imperfect, but who is forced to absorb the consequences of their imperfections.

Power, Scale, and Asymmetry

Algorithmic governance systems do not emerge in a vacuum. They are adopted within institutional contexts defined by asymmetries of power, expertise, and resources. Governments and public agencies increasingly rely on automated systems not only to manage complexity, but to compensate for structural constraints: understaffing, budgetary pressure, political timelines, and the demand for rapid decision-making at scale.

In this environment, technology vendors play a decisive role. Complex algorithmic systems are frequently procured as turnkey solutions, developed and maintained by private companies whose models, data pipelines, and evaluation methods remain proprietary. Public institutions may purchase operational capacity without acquiring meaningful control over how decisions are produced (Oxford Internet Institute) .

This creates a structural imbalance. While algorithmic systems exert binding effects on citizens, the knowledge required to audit, contest, or modify them is often concentrated outside democratic institutions. Oversight bodies, courts, and regulators may lack both technical access and institutional authority to fully interrogate these systems, particularly when intellectual property claims are invoked to limit disclosure.

Scale further amplifies this asymmetry. Once deployed, automated systems can affect tens or hundreds of thousands of individuals with minimal marginal cost. Errors, biases, or flawed assumptions therefore propagate rapidly, while mechanisms for redress remain individualized, slow, and resource-intensive. As a result, systemic harm can persist long after problems are identified.

Political incentives also shape adoption. Automated decision-making systems are frequently framed as neutral, objective, or efficiency-enhancing tools, allowing policymakers to present contentious decisions as technical necessities rather than political choices. This framing can reduce accountability by shifting responsibility from human decision-makers to systems portrayed as impartial (MIT Technology Review) .

At the same time, affected individuals face profound informational disadvantages. They may be unaware that an algorithmic system influenced a decision, unable to access the logic behind it, or uncertain about which institution bears responsibility. In such conditions, the right to explanation or appeal risks becoming formal rather than effective.

Taken together, these dynamics reveal that algorithmic control is not merely a technical phenomenon, but a redistribution of power. Authority is shifted away from front-line officials and public deliberation toward centralized systems whose design choices are rarely subject to democratic scrutiny.

The central challenge, therefore, is not simply improving model accuracy or reducing bias. It is addressing the asymmetry between those who design, deploy, and profit from algorithmic systems, and those who live under their decisions—often without visibility, voice, or recourse.

Regulation, Rights, and the Limits of Transparency

In response to the growing influence of algorithmic systems in public decision making, regulators—particularly in the European Union—have begun to develop legal frameworks aimed at restoring accountability. Instruments such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the proposed AI Act represent some of the most ambitious attempts globally to govern automated decision systems.

Under the GDPR, individuals have the right not to be subject to decisions based solely on automated processing when those decisions produce legal or similarly significant effects (Article 22, GDPR) . The regulation also establishes rights to information, access, and contestation. In theory, these provisions offer a legal foundation for resisting opaque algorithmic governance.

In practice, however, these rights have proven difficult to operationalize. Automated systems are often embedded within hybrid decision processes that include nominal human oversight, allowing institutions to argue that decisions are not fully automated—even when human involvement is minimal or procedural. This interpretation significantly narrows the scope of legal protections.

Transparency requirements face similar limitations. While regulations may mandate disclosure of decision logic or system purpose, the information provided is frequently abstract, incomplete, or inaccessible to non-experts. High-level descriptions of algorithmic processes rarely enable affected individuals to understand how specific inputs influenced a particular outcome (Oxford Internet Institute) .

The emerging EU AI Act seeks to address some of these shortcomings by imposing risk-based obligations, particularly for systems used in areas such as law enforcement, migration, creditworthiness, and social services. High-risk systems would be subject to stricter requirements around documentation, human oversight, and post-deployment monitoring (European Commission) .

Yet even these measures confront structural constraints. Effective oversight requires technical capacity, institutional independence, and access to underlying system components—conditions that are not uniformly present across member states. Without sustained investment in regulatory expertise, compliance risks becoming procedural rather than substantive.

Moreover, transparency alone does not resolve the deeper problem of power asymmetry. Knowing that an algorithm influenced a decision does not automatically grant the ability to challenge it, particularly when legal, economic, or informational barriers remain high. As several scholars have argued, transparency without enforceable accountability may offer visibility without remedy (Big Data & Society) .

The regulatory challenge, therefore, is not only to make algorithmic systems visible, but to render them contestable. This requires mechanisms that allow decisions to be questioned, reversed, or suspended, and institutions to be held responsible when automated systems cause harm.

As algorithmic governance expands, the gap between formal rights and lived experience risks widening. Bridging that gap will determine whether regulation functions as a meaningful safeguard—or as a symbolic gesture in the face of increasingly automated power.

Reclaiming Agency in an Automated Society

The expansion of algorithmic systems into governance, markets, and public services raises a fundamental question: how can democratic agency be preserved in an environment increasingly shaped by automated decision-making?

Reclaiming agency does not require rejecting technology, nor does it depend on perfect transparency or total system explainability—goals that may remain technically elusive in complex machine learning models. Instead, it requires reframing governance around power, responsibility, and institutional control.

First, algorithmic systems that influence rights, access to resources, or opportunities must remain subject to meaningful human authority. Human oversight cannot be symbolic or procedural; it must include the capacity to intervene, override, and suspend automated processes when harm or error is identified. Without this capacity, oversight becomes an administrative fiction.

Second, accountability must extend beyond individual decisions to system-level outcomes. Harm produced by automated systems is often cumulative and distributed, emerging from patterns rather than isolated events. Regulatory and judicial mechanisms must therefore be capable of addressing structural effects, not only individual complaints (Ada Lovelace Institute) .

Third, public institutions require independent technical capacity. Oversight cannot rely exclusively on documentation provided by system developers or vendors. Auditing, impact assessment, and post-deployment monitoring must be supported by expertise that is both adequately resourced and institutionally autonomous (AlgorithmWatch) .

Crucially, agency is also a social and political condition. Individuals affected by algorithmic decisions must have accessible pathways to contest outcomes, obtain explanations that are meaningful in context, and seek redress without disproportionate burden. Legal rights that exist only in theory do little to counterbalance automated power.

At a broader level, societies must confront the political choices embedded in automation. Decisions about where algorithms are deployed, which objectives they optimize, and whose values they encode are not technical inevitabilities. They are matters of governance, priority, and democratic deliberation.

The risk facing contemporary societies is not that machines will replace human judgment, but that judgment will quietly retreat—ceded to systems perceived as neutral, efficient, or inevitable. Algorithmic control rarely announces itself as domination. It emerges through normalization.

Preserving agency in an automated society therefore demands vigilance rather than panic, structure rather than slogans, and governance rather than faith in technical solutions. The specter in the machine is not intelligence itself, but the abdication of responsibility behind it.