Is the AI Bubble Real? Hype, Capital, and Governance in 2025

Is the AI bubble real? As investment in artificial intelligence reaches unprecedented levels in 2025, warnings of an emerging “AI bubble” are once again dominating global headlines. Trillions of dollars are flowing into foundation models, semiconductor supply chains, and hyperscale data centers, while governments race to position AI as a strategic economic and geopolitical asset.

From soaring private valuations and aggressive infrastructure expansion to fears of overcapacity, labor disruption, and market concentration, the debate has intensified across financial markets, policy circles, and the technology industry. Comparisons to the dot-com collapse of the early 2000s are increasingly common — yet many analysts argue that today’s AI boom differs fundamentally from past speculative cycles.

The central question is no longer whether artificial intelligence will reshape economies — that transformation is already underway — but whether the current acceleration reflects an unsustainable financial bubble or a deeper structural shift whose primary risks lie not in collapse, but in governance, regulation, and institutional readiness.

In 2025, understanding this distinction has become critical. Misdiagnosing systemic transformation as mere hype risks regulatory paralysis, while ignoring genuine financial excess could amplify future instability. The tension surrounding AI may ultimately prove less technological than political.

MindPulse Editorial Note: At MindPulse, we approach the “AI bubble” debate with caution toward simplified narratives. History suggests that transformative technologies often arrive accompanied by speculative excess — but also that regulatory blind spots and governance failures can pose deeper, longer-lasting risks than market corrections.

Our analysis focuses not only on capital flows and valuations, but on the growing governance gap shaping the AI era: the divergence between rapid technological deployment and the slower evolution of legal, ethical, and institutional frameworks. The true risk may not be an AI crash, but an uncoordinated global response to a technology already embedded in critical infrastructure.

Why the AI Boom Feels Like a Bubble

The perception of an “AI bubble” is not emerging in a vacuum. In many respects, today’s artificial intelligence landscape exhibits the classic signals that have historically accompanied speculative cycles: rapid capital inflows, ambitious projections, and an accelerating race to scale infrastructure ahead of clearly defined demand.

Since 2022, venture capital investment in AI-related companies has surged, while the market capitalization of leading technology firms has become increasingly tied to their AI narratives. Hyperscale cloud providers and semiconductor manufacturers are committing tens of billions of dollars to data center expansion, often justified by anticipated future workloads rather than current utilization.

This gap between present capabilities and future expectations is where bubble concerns typically take root.

Similar patterns were visible during the dot-com boom: infrastructure was built ahead of mass adoption, valuations were driven by narrative dominance rather than cash flow, and market leaders absorbed disproportionate amounts of capital. In hindsight, many of those investments proved premature — though not entirely misguided.

In the AI context, critics point to several recurring warning signs:

- Valuation inflation: Startups with limited revenue streams commanding multibillion-dollar valuations based largely on model scale or data access.

- Infrastructure overbuild: Data center capacity expanding faster than near-term enterprise demand for advanced AI workloads.

- Concentration risk: A small number of firms controlling the majority of compute, models, and deployment pipelines.

- Unclear monetization paths: Persistent uncertainty around how many generative AI applications will translate into sustainable profits.

These dynamics have fueled skepticism among economists and market analysts who argue that artificial intelligence, while powerful, may be overcapitalized relative to its immediate economic output.

Yet this framing risks oversimplification. Historical comparisons can illuminate patterns, but they can also obscure critical differences between speculative hype and structural technological change.

Why This Cycle Is Structurally Different

While comparisons to past technology bubbles are tempting, artificial intelligence differs from previous speculative waves in several fundamental ways. The most important distinction is that AI is not a single product category or platform — it is an enabling layer that is rapidly embedding itself across the entire economic and institutional stack.

Unlike consumer internet startups of the early 2000s, today’s AI expansion is being driven not only by venture capital, but by sovereign interests, industrial policy, and long-term infrastructure commitments from both governments and multinational corporations.

This matters because it changes the risk profile.

Large-scale investments in compute, energy, and semiconductor supply chains are not speculative in the same sense as consumer-facing web platforms once were. They are tied to national competitiveness, defense capabilities, scientific research, and economic resilience.

In practice, this has produced three structural characteristics that set the AI boom apart:

- State involvement: Governments increasingly view AI capacity as strategic infrastructure, comparable to energy grids or telecommunications networks.

- High capital inertia: Once built, data centers, fabs, and power infrastructure cannot simply be abandoned without significant economic and political cost.

- Cross-sector dependency: AI capabilities are now embedded in logistics, finance, healthcare, defense, and public administration — not isolated consumer markets.

This does not eliminate the possibility of overinvestment or market correction. It does, however, suggest that any adjustment is more likely to take the form of consolidation, regulatory intervention, or shifts in governance rather than a sudden collapse.

In this sense, the dominant risk facing artificial intelligence is not a bursting bubble, but a misalignment between technological power and the institutions responsible for managing it.

Capital, Power, and the AI Infrastructure Race

Beneath the surface of consumer-facing AI products, a far more consequential race is underway. The defining feature of the current AI cycle is not software innovation alone, but the rapid construction of physical and institutional infrastructure required to sustain it.

Data centers, advanced semiconductor fabrication plants, specialized networking hardware, and vast energy resources have become the true choke points of artificial intelligence. Control over these assets increasingly determines who can build, deploy, and govern advanced AI systems.

Over the past two years, investment in AI-related infrastructure has accelerated dramatically. Major technology firms have committed tens of billions of dollars to new data centers, long-term power purchase agreements, and custom silicon development. At the same time, governments have begun treating compute capacity as a matter of national strategy.

This convergence of private capital and public interest marks a turning point.

In the United States, Europe, and parts of Asia, AI infrastructure is now entangled with industrial policy, energy planning, and national security frameworks. Semiconductor supply chains are being reshaped through subsidies and export controls, while access to advanced chips has become a geopolitical instrument.

The result is a landscape defined by concentration rather than openness.

- Compute concentration: A small number of firms control the majority of frontier-scale training capacity.

- Energy dependence: AI expansion is increasingly constrained by access to reliable, large-scale electricity generation.

- Vertical integration: Leading players are integrating hardware, models, platforms, and distribution under unified control.

This concentration has economic consequences. Smaller firms and public institutions often rely on access mediated by dominant platforms, reinforcing asymmetries in bargaining power, pricing, and governance influence.

From this perspective, the AI boom resembles less a speculative frenzy and more a global infrastructure buildout — one that redistributes power toward those who control the physical foundations of computation.

The critical question, then, is not whether too much money is flowing into AI, but who ultimately controls the systems that money is building.

Labor, Productivity, and the Myth of Immediate Displacement

Few narratives surrounding artificial intelligence generate as much anxiety as the prospect of widespread job loss. Headlines warning of imminent mass unemployment have become a recurring feature of the AI discourse, often framing automation as an abrupt and uncontrollable force.

Yet historical precedent and current labor data suggest a more complex reality.

Technological revolutions rarely eliminate work outright. Instead, they reconfigure tasks, redistribute skills, and reshape productivity across sectors. The AI transition appears to follow this pattern, though at a pace and scale that challenge existing institutions.

What AI automates most effectively today is not jobs, but components of jobs.

In fields such as software development, finance, legal services, and media, AI systems increasingly handle routine or repetitive cognitive tasks — code refactoring, document summarization, data analysis, and first-pass drafting. Human labor, rather than disappearing, shifts toward oversight, integration, judgment, and creative synthesis.

This shift produces measurable productivity gains. Multiple studies and industry reports indicate that AI-assisted workers often complete tasks faster and with fewer errors, particularly when AI tools are deployed as complements rather than replacements.

However, productivity gains are not evenly distributed.

- High-skill augmentation: Workers with domain expertise tend to benefit most from AI assistance.

- Entry-level pressure: Roles traditionally used for training and skill acquisition face increased automation risk.

- Organizational asymmetry: Firms able to invest in AI integration capture disproportionate efficiency gains.

These dynamics introduce a subtler risk than mass unemployment: a hollowing of career ladders and an acceleration of inequality within knowledge-based professions.

Warnings from prominent AI researchers and economists often reflect this concern. The issue is not that work disappears overnight, but that labor markets may struggle to absorb structural change without deliberate policy intervention.

Education systems, reskilling programs, and labor protections were designed for slower technological cycles. AI compresses timelines, creating transitional shocks that existing institutions are ill-equipped to manage.

Framing AI as a simple job-destroying force obscures the deeper challenge: aligning productivity gains with social stability, economic mobility, and meaningful work.

In this sense, the labor question reinforces a central theme of the AI era — progress without governance does not fail spectacularly; it erodes quietly.

Is This an AI Bubble — or a Misdiagnosed Transition?

To assess whether artificial intelligence is experiencing a speculative bubble, it is necessary to define what a bubble actually entails. In economic terms, bubbles are characterized by inflated valuations disconnected from underlying utility, followed by a rapid collapse when expectations fail to materialize.

At first glance, today’s AI landscape appears to fit parts of this pattern: soaring corporate valuations, aggressive capital deployment, and intense competition to secure scarce resources such as compute, data, and talent.

Yet this comparison breaks down under closer inspection.

Unlike purely speculative assets, AI systems are already delivering measurable operational value across multiple sectors. Enterprises deploy machine learning models to optimize logistics, accelerate research, reduce costs, and augment professional labor. Governments increasingly rely on AI for analysis, forecasting, and administrative efficiency.

This is not a market built on hypothetical demand.

The infrastructure being constructed — data centers, specialized chips, cloud platforms — supports active and growing workloads. Even if growth rates fluctuate, the underlying demand for computational intelligence is unlikely to vanish.

Historical analogies are instructive. The railway boom of the 19th century, the electrification of industry, and the early internet era all experienced periods of overinvestment, followed by consolidation rather than collapse.

In each case, capital raced ahead of governance.

The dot-com crash is often cited as a cautionary tale, but its aftermath produced durable infrastructure — fiber networks, protocols, platforms — that enabled the modern digital economy. The speculative layer collapsed; the structural layer endured.

AI appears to follow a similar trajectory.

Some ventures will fail. Some valuations will correct. Overcapacity in certain segments, particularly speculative applications without clear integration pathways, is likely. But these outcomes reflect market selection, not systemic collapse.

The deeper risk lies elsewhere.

Mislabeling AI as a bubble obscures the true challenge: governance lag.

While capital allocation can self-correct through market mechanisms, governance failures persist. Concentration of compute, opacity in model deployment, environmental strain from data centers, and uneven access to AI capabilities create long-term structural imbalances.

A bubble bursts quickly. Institutional gaps widen slowly.

Framing AI primarily as a speculative excess risks delaying necessary policy responses. The question is not whether investment levels are justified, but whether institutional frameworks are evolving fast enough to manage an increasingly infrastructural technology.

In this sense, the AI moment is less a bubble than a stress test — exposing the limits of existing economic, regulatory, and social systems.

Capital, Compute, and the New AI Power Stack

As artificial intelligence matures, its center of gravity is shifting away from software alone and toward physical and financial infrastructure. Compute capacity, energy access, land, and capital now form the backbone of competitive advantage in the AI economy.

This transformation has profound implications for power distribution.

Training and operating large-scale AI systems requires vast data centers, specialized semiconductor supply chains, and long-term energy commitments. These requirements place meaningful constraints on who can participate at the frontier of AI development.

AI is no longer just a code problem — it is an infrastructure problem.

A small number of corporations and investment groups now control disproportionate shares of global compute capacity. Access to advanced chips, cloud-scale training environments, and proprietary datasets increasingly determines strategic relevance.

This consolidation mirrors earlier phases of industrialization, where ownership of railways, oil fields, or electrical grids translated into enduring economic and political influence.

Recent acquisition activity and capital flows underscore this shift. Investment is concentrating not only in model development, but in the assets that enable models to exist at scale: data centers, networking infrastructure, and energy-intensive facilities.

Governments are beginning to recognize this dynamic. In policy discussions across the United States, the European Union, and parts of Asia, AI infrastructure is increasingly framed as a strategic resource rather than a neutral commercial asset.

This reframing introduces new tensions.

- National security: Control over compute becomes linked to technological sovereignty.

- Market power: Infrastructure concentration risks entrenching monopolistic advantages.

- Environmental impact: Energy and water demands of AI data centers raise sustainability concerns.

Unlike software markets, infrastructure investments are difficult to unwind. Once built, data centers and power agreements lock in long-term dependencies that shape policy choices for decades.

This reality complicates the “bubble” narrative. Infrastructure-driven systems do not collapse easily; they persist, even if utilization fluctuates.

The question, then, is not whether too much capital has entered AI, but who controls the layers beneath the algorithms — and under what rules.

As AI becomes embedded in critical economic and governmental functions, infrastructure ownership increasingly translates into agenda-setting power.

In the absence of clear governance frameworks, this concentration risks transforming AI from a broadly enabling technology into a gatekept resource.

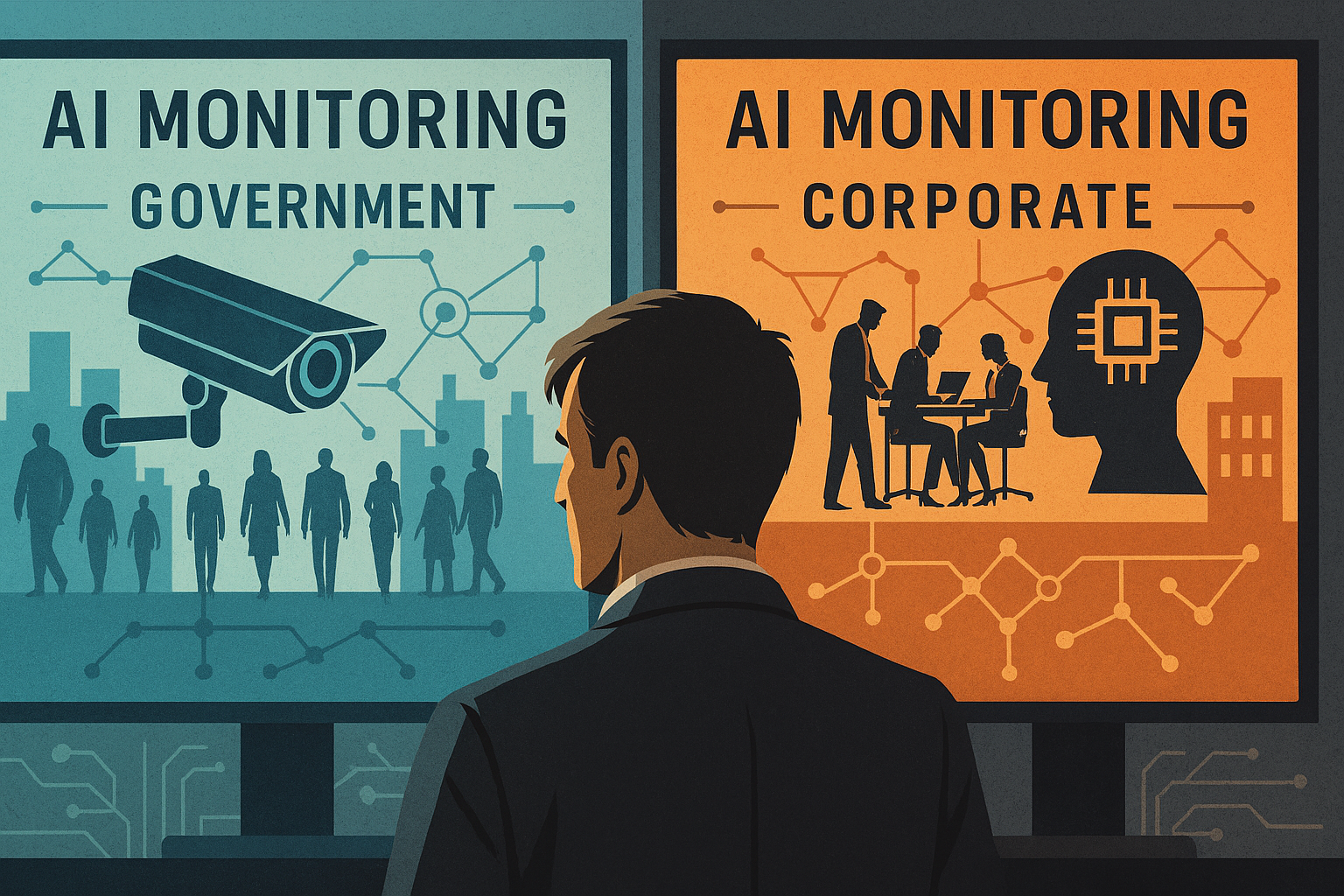

Governance Lag: When Regulation Trails Reality

If the defining feature of the current AI moment is acceleration, its most persistent weakness is institutional lag. While capabilities, investment, and deployment scale rapidly, governance frameworks evolve far more slowly.

This mismatch has become increasingly visible throughout 2025.

Across jurisdictions, governments struggle to reconcile the speed of AI development with legal systems designed for incremental change. As a result, regulation often arrives fragmented, reactive, or misaligned with the technologies it seeks to govern.

The global governance landscape is diverging rather than converging.

In broad terms, the European Union continues to frame AI primarily through civil and regulatory lenses — emphasizing consumer protection, transparency obligations, and systemic risk classification. The EU’s AI Act reflects an attempt to embed AI oversight within existing legal traditions.

By contrast, the United States increasingly approaches AI through the prism of national security and strategic competition. Executive actions, export controls, and defense-oriented funding initiatives position AI as a geopolitical asset rather than a regulated public technology.

This divergence creates a fragmented global environment in which companies navigate overlapping, and sometimes conflicting, regulatory expectations.

At the same time, much of the AI ecosystem operates in spaces that regulation barely touches: model training opacity, proprietary datasets, infrastructure ownership, and private-sector deployment decisions with public consequences.

The result is a governance gap — not an absence of rules, but a misalignment between where power resides and where oversight is applied.

Regulatory efforts often focus on downstream applications, while upstream control over compute, model architecture, and deployment incentives remains largely unchecked.

This imbalance carries systemic risks.

- Accountability gaps: When harms occur, responsibility is diffuse and difficult to assign.

- Regulatory arbitrage: Firms shift operations across jurisdictions to minimize oversight.

- Democratic strain: Decisions with societal impact migrate from public institutions to private infrastructure owners.

Importantly, governance lag does not produce immediate failure. It produces gradual erosion — of trust, legitimacy, and public capacity to steer technological outcomes.

AI’s power lies not only in what it can do, but in how quietly it integrates into systems of decision-making. When governance trails reality, control shifts by default rather than by design.

Addressing this lag requires more than compliance checklists. It demands institutional innovation — new forms of oversight, cross-border coordination, and technical literacy within regulatory bodies.

Without such adaptation, governance risks becoming symbolic, while real authority consolidates elsewhere.

Environmental and Social Externalities: The Hidden Costs of Scale

As artificial intelligence systems scale, their physical footprint has become impossible to ignore. Behind abstract discussions of models and algorithms lies a rapidly expanding network of data centers, energy infrastructure, water consumption, and land use.

In 2025, this material dimension of AI moved decisively into the public debate.

Large-scale data centers now rank among the most energy-intensive industrial facilities in operation. Their demand for continuous power, cooling, and connectivity places strain on local grids and water systems, particularly in regions already facing resource constraints.

What was once framed as a digital industry is increasingly experienced as a territorial one.

Communities hosting AI infrastructure face tangible trade-offs: increased energy prices, environmental stress, and limited local economic return relative to the scale of investment. In many cases, decisions about siting and expansion occur with minimal public consultation.

This has begun to generate political friction.

Environmental groups, local governments, and labor organizations have raised concerns about the sustainability of unchecked AI infrastructure growth. These debates intersect with broader anxieties about inequality, climate commitments, and democratic accountability.

The tension is not simply about technology, but about distribution.

- Who bears the environmental cost of AI-scale computation?

- Who captures the economic value generated by these systems?

- Who has a voice in decisions about deployment and expansion?

These questions have no purely technical answers. They sit at the intersection of infrastructure policy, environmental regulation, and social contract.

Importantly, such externalities do not imply that AI infrastructure is inherently unsustainable. Rather, they reveal the absence of governance mechanisms capable of aligning technological expansion with environmental limits and social consent.

Without transparent planning, shared benefits, and enforceable standards, infrastructure growth risks provoking backlash that could slow deployment through political resistance rather than deliberate design.

In this sense, environmental and social pressures function as early warning signals — not of technological failure, but of institutional misalignment.

Labor, Productivity, and the Risk of a Jobless Boom

Few dimensions of artificial intelligence generate as much public anxiety as its impact on work. Throughout 2025, warnings about large-scale job displacement intensified, driven not by speculative forecasts but by observable shifts in professional labor markets.

Advances in AI-assisted software development, automated analysis, and decision-support systems have begun to affect roles once considered insulated from automation. Productivity gains are real — but their distribution remains deeply uneven.

This raises a critical distinction: productivity growth does not automatically translate into broad-based employment growth.

Historically, technological revolutions eventually generated new categories of work. However, AI differs in that it targets cognitive and coordination tasks across multiple sectors simultaneously, compressing adjustment timelines.

In 2025, several leading researchers and economists warned of a potential “jobless boom” — a period in which output and efficiency rise while employment stagnates or declines, particularly in white-collar professions.

The risk is not immediate mass unemployment, but structural imbalance.

- Skill polarization: High-value AI-adjacent roles expand, while mid-level professional tasks erode.

- Wage pressure: Automation leverage shifts bargaining power toward capital owners and platform operators.

- Institutional stress: Labor markets adjust faster than education systems, retraining programs, and social protections.

Importantly, these dynamics are shaped as much by policy choices as by technology itself.

Decisions about taxation, workforce transition support, collective bargaining, and public investment will determine whether AI-driven productivity amplifies inequality or contributes to shared prosperity.

Absent proactive intervention, labor displacement risks becoming a political flashpoint rather than an economic adjustment — fueling distrust toward institutions perceived as prioritizing efficiency over social stability.

In this context, the central question is not whether AI will change work, but whether societies are prepared to manage that change deliberately rather than reactively.

Conclusion: Beyond the Bubble Narrative

Framing artificial intelligence purely through the lens of a speculative “bubble” risks obscuring the deeper structural forces now reshaping the global economy. While warning signs are real — inflated valuations, unprecedented capital expenditure, and aggressive infrastructure expansion — today’s AI boom cannot be reduced to a simple replay of the dot-com era.

Unlike previous technology cycles, artificial intelligence is already embedded in critical systems: cloud infrastructure, national security, scientific research, logistics, and knowledge production itself. As MIT Technology Review has noted, AI’s current phase is less about consumer hype and more about the consolidation of foundational capabilities — compute, data, and models — in the hands of a small number of actors (MIT Technology Review).

This distinction matters. Market corrections may occur — and historically, they almost always do — but a correction would not undo the structural role AI now plays. As The Economist has argued, the greater risk is not a collapse in valuations, but a mismatch between the speed of deployment and the institutions meant to govern it (The Economist).

Nowhere is this tension clearer than in the emerging global governance divide. The European Union has positioned itself as the world’s first comprehensive AI regulator through the EU AI Act, emphasizing civil rights, systemic risk, and accountability (European Commission). By contrast, the United States has framed AI primarily through the lenses of national security, strategic competition, and industrial policy — a stance reflected in executive orders, defense funding priorities, and restrictions on advanced semiconductor exports (White House).

This divergence represents a growing governance gap, not merely a regulatory disagreement. As AI systems scale globally, fragmented oversight risks creating uneven protections, regulatory arbitrage, and escalating geopolitical tension. Wired has repeatedly warned that without shared norms, AI development may drift toward concentration and opacity rather than transparency and public trust (Wired).

From an economic perspective, even bullish analysts acknowledge uncertainty. Goldman Sachs has highlighted the unprecedented scale of AI-related capital expenditure — particularly in data centers and energy infrastructure — while cautioning that productivity gains may take longer to materialize than markets currently assume (Goldman Sachs Insights). This lag, more than speculation itself, may define the next phase of the AI cycle.

The central question, then, is not whether the AI bubble is “real,” but whether institutions can evolve fast enough to match the power they are helping unleash. Technological revolutions rarely fail because the technology proves useless. They falter when governance, accountability, and social adaptation lag too far behind.

In that sense, the most dangerous illusion is not overconfidence in AI’s potential, but complacency about how it is steered.

MindPulse Editorial Note

At MindPulse, we see artificial intelligence neither as an inevitable utopia nor an unavoidable threat. It is a force multiplier — one that amplifies existing economic incentives, political priorities, and cultural values.

The debate around an “AI bubble” is useful only insofar as it opens a broader conversation about responsibility, governance, and long-term alignment. Capital will continue to flow. Models will continue to scale. What remains undecided is whether AI’s expansion will be guided by coherent frameworks and shared values — or by short-term competition alone.

The future of AI will not be determined by hype cycles, but by the quality of the choices made now.